Barn owl (Tyto alba) populations in North America have been declining rapidly for the past two decades primarily due to limited accessibility of hollow trees, old barns, silos and suitable grassland habitat. Other reasons for declining barn owl populations include: use of pesticides and rodenticides, predation by great horned owls and suburban expansion. The barn owl is currently on the threatened species list in Pennsylvania, so numerous citizen science initiatives, such as this project, have been proposed and launched to help observe breeding, nesting and fledging behaviors. Results from these types of initiatives will help educate landowners about how to maintain or increase barn owl populations.

This spring marked the first year Shaver’s Creek Environmental Center and members of the public had the opportunity to observe a pair of barn owls raise young via webcam. Two webcams were mounted both inside and outside the nest box for 24/7 observations of barn owl activities from March 27 through July 7, with only the inside camera viewable to the public. One staff member and three volunteers observed nocturnal footage the following morning and noted food deliveries, copulation, nestling growth, and any noteworthy behavior. Observations of the entire nesting season gave observers great insight into the daily activities of an experienced barn owl pair as they raised their young in a well-managed habitat that provided suitable nesting and hunting opportunities.

Incubation

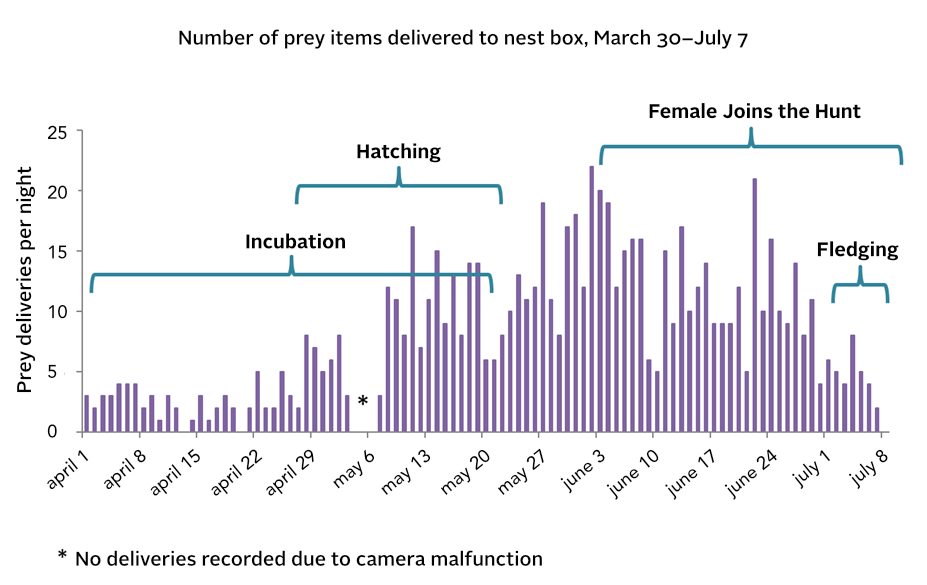

When the webcam was installed on March 27, three eggs had already been laid in the nest box. Over the next 10 days, four additional eggs were laid. A typical barn owl clutch ranges from 3-11 eggs and the pair’s clutch of seven was well within the expected range. Incubation was done solely by the female with the male providing food to the female throughout the nocturnal hours (Figure 1). The male was absent from the nest box during diurnal roosts and was observed roosting in an nearby abandon silo by staff and landowners during the day. Before any owlets hatched, we noticed that the female took very brief breaks from incubation, roughly 15-20 minutes per evening, to possibly stretch or signal to male counterpart for food or copulation needs. Toward the end of April and into early May, as hatching occurred, food delivery by the male increased. At this time, the female was observed piling up prey around her as if to “feather” the nest with a food supply for the hatching owlets.

Interestingly, copulation behavior was observed from late March through mid-May even after eggs were laid and especially before young began to hatch. Copulation occurred up to nine times per evening. When the male brought prey to the incubating female, she would beg for food and signal her desire to mate. The male would respond to her calls and copulate with her and on rare occasions, she would deny his advances. About 90% of the time when the male brought prey for the female, she would accept his advances. Multiple copulations after fertilized eggs are laid seems to be a waste of energy; however, this would be advantageous if any of the eggs in the clutch are preyed upon or damaged. Of course, with the increase in copulatory acts and the rapidly-approaching egg hatching times, food deliveries and frequencies vastly increased.

Hatching

All seven eggs hatched over an extended period of 25 days between April 24 and May 18 with the first 5 hatchlings emerging over a nine-day period. The final two hatchlings emerged over the last fifteen days. Owls, like other raptors, undergo asynchronous egg laying and hatching. Eggs are laid one at a time over several weeks and likewise, owlets hatch one at a time over a period of several weeks to 30 days. The advantages of asynchronous hatching assist the owl parents in raising the largest number of offspring that can be supported by unpredictable prey populations and that this strategy allows for survival of the most fit owlets. The disadvantages of asynchronous hatching are that if the in-coming prey supplies are not sufficient for the entire owl brood, the older larger siblings will either out-compete the younger, weaker siblings for food or the oldest siblings will cannibalize the youngest sibling, resulting in a smaller number of owlet fledglings.

Although the barn owl pair were experienced or efficient parents and appeared to be quite successful in bringing prey to the owlets, the youngest, smallest owlet was observed deceased in the nest box on May 25. Although the true cause of death was unknown, it appeared to be too small to successfully compete for food and space with the large number of bigger siblings. Observers also noted as the nestlings grew in size, nest box space became limited and the female parent reduced her diurnal roosting time in the box. Therefore, prey brought to the box the night prior was not given the attention needed to be torn apart for feeding by female. The fact that six out of the seven owlets survived to fledging in a crowded nest box is a testament to the skills of their parents and abundance of prey items.

From our observations, the male was the sole food provider until early June. The female remained in the nest box with the hatchlings, tearing apart delivered food items and feeding the bits to the young. In early June, when the third owlet was large enough to feed itself. The female began assisting the male with food delivery to the brood. This increased the number of prey items delivered as well as feeding the owlets excessive food items from previous hunts.

Feeding

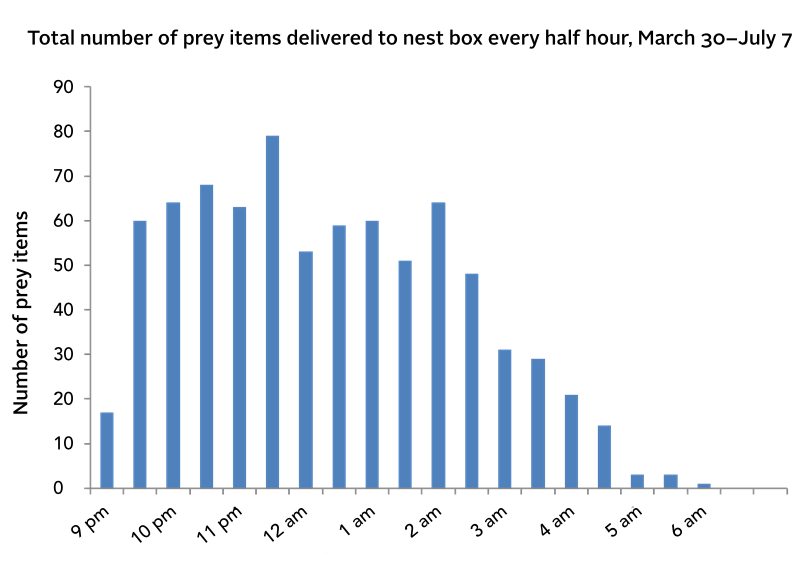

Barn Owls are strictly nocturnal hunters, which take advantage of their optimally designed facial disk (or ruff) to locate prey in darkened conditions. Our observations showed that peak feeding times occur from 10:00pm-11:30pm and midnight to 2:00am (Figure 2). Clear, dry and moonlit skies are the most optimal conditions for hunting, as nocturnal creatures take advantage of foraging opportunities. Overcast, rainy and stormy weather decreases feeding frequencies and quantities of food delivered to the owlets. Variable weather conditions may help to explain some of the nightly variation in prey delivery to the nest box that we observed.

A wetter-than-average spring that occurred in this region of the state may have increased available prey items allowing the pair to take advantage of the bounty. Although number of prey were recorded, no identification of rodent species were noted, but in some instances observers were able to identify one song sparrow, two starlings, peromyscus sp, and large rats. A total of 788 food items were noted as food deliveries from male to incubating female or from parent to nestling. This is an underestimate of the actual number delivered due to observations starting after the third egg was laid; power outage that occurred for four days (May 4-May 7); multiple camera malfunctions; and unknown number prey items consumed by foraging parent. Despite the inability to observe the entire nesting season and observe foraging behavior outside the nest box. Observations from this spring provided an astonishing sense of the significance barn owls can play in the consumption of rodents in a given habitat.

Fledging

Owlets are not pushed out of their nest site by their parents. Growth hormones surge in adolescent owlets, signaling when they are ready to fledge. Their wings are fully developed; however, they are not strong enough for sustained flight, so owls will “branch” from one potential landing or perching site to the next to build up flight endurance. Using an outside camera near the nest box entrance, observers noted owlets perched upon the entranceway opening on the outside of the nest box and held on until they were ready to leap upon two man-made platforms mounted outside of the nest box. At this time, the nestlings flapped their wings to build strength and to practice take-off and landing techniques. These “flight school” practices were observed over a 10-day period beginning with the first four fledges occurring on June 29 and June 30, with the last fledging on July 7. Typically, the three or four oldest siblings who learned to fly first would be out most of the evening foraging and then return before dawn to join the youngest siblings for diurnal roosting. Early July the oldest siblings eventually began roosting outside of the nest box at an unknown location. Mid-July, the youngest siblings followed suit. The oldest sibling typically left about a few days earlier than the next oldest sibling around 9-12 weeks of age. Observers noted that all owlets did not leave for permanently until the youngest sibling fledged around mid-July.

Acknowledgments

With the seasons transitioning into fall, barn owls from 2019 nesting season are dispersing through the landscape and the nest boxes are quiet of any owl activity. The first season of live video feed increased awareness not only to staff and like-minded educators but also to those at home to gain a better appreciation of the challenges barn owl face in successfully rearing young. Although the nesting season has past, it is time to start thinking of ways to continue the success for the 2020 nesting season.

A big thank-you to the private landowners for providing the opportunity to share the seasons nesting success of barn owls to the community at large and providing suitable nesting and foraging opportunities. Thank you to volunteers Carolyn Muse, Lou Saporito, Alison Cook, Graham Gorgas, and Peggy Wagoner Saporito for contributions of their time perusing through video, camera technical help, and complying the season summary.

Funding for this project and other STEM activities provided by the M. W. McBride endowment for Shavers Creek.

An incredibly fascinating and illuminating piece, Carolyn. Thank you!