Species are often depicted in books and movies with the same characteristics. There are the wise old owls, such as Owl from Winnie the Pooh, and the friendly heroic dogs, such as Lassie. But have you ever wondered why we give these specific features to certain animals? Animythology is my attempt to explore this topic by comparing the traits of these animals to their actual behavior. Today, I’m looking at one of my personal favorite animals, the corvid.

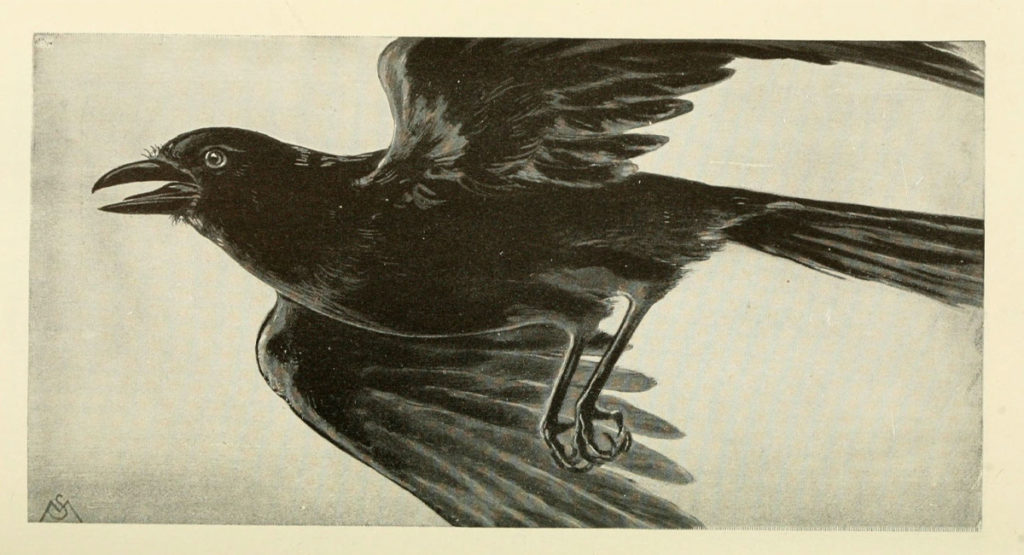

Corvids are a family of passerine, or perching birds, that includes crows, ravens, blue jays, and magpies. For the sake of simplicity, I’ll focus on crows and ravens. Crows and ravens are two of the few species that live on every continent except Antarctica. Even without a foothold in the polar continent, they display a remarkable ability to exist in most climates, being equally common in tundra and deserts. Even more remarkably, corvids have been able to thrive in areas of high human population, with some species, such as the Japanese House Crow, exclusively nesting in human-made structures. Because they’re so ubiquitous, it’s no wonder that corvids are richly depicted across cultures.

The Divine Messenger

Many Western myths prominently feature ravens as divine messengers. One example comes from Norse mythology. Odin, God of Wisdom and Magic, was accompanied by two ravens named Huginn and Muninn, which translate as Thought and Memory. Odin would send Huginn and Muninn across the world, where they would spy on humans and bring him news.

Some precedence for this motif exists. Ravens display a fascinating capacity for language, being able to communicate complex concepts to each other. While most animals can communicate, they’re usually limited to simple ideas like “food is here” or “I want to mate.” Corvids, however, are able to convey more complex ideas in different social situations, with studies showing that a crow communicates with its family in a softer, slower tone than with a neighboring crow — think of how you might talk with a close friend compared to a stranger.

Ravens have also demonstrated clear body language when talking with other ravens, something not present during interactions with other birds or people. In addition, corvids are capable of not only saying simple words or phrases in human languages, but also understand the words’ meaning.

The Trickster

The crow and raven are also represented as tricksters. The crow is an important figure in Aboriginal mythology and is responsible for bringing fire to mankind. In Aboriginal myth, fire was a secret guarded jealously by the seven Karatgurk — the seven sisters who represent the constellation Pleiades. Crow noticed how the Karatgurk used fire to cook yams and asked if they would share with him, only to be refused.

Rejected, Crow caught and buried snakes in an ant mound and told the sisters that he had discovered delicious larva in the mound — tastier than any cooked yam. The sisters dug up the mound and were attacked by the snakes. During the confusion, Crow stole hot coals from the fire. Crow retreated back to his nest, and soon other animals noticed how tasty Crow’s cooked yams were. The other animals demanded Crow cook their food over the fire. He soon grew tired and tossed the coals to the crowd, burning his feathers black and giving fire to the world.

Corvids are notorious pranksters in real life. Often, a murder — a group of crows — will annoy other birds for the fun of it. Pulling the tail of a larger bird is a common prank enjoyed by many corvids. Corvids also enjoy playing. They have been observed using their beaks to have snowball fights. And ravens play a game by dropping a stick mid-air and racing to catch it before it hits the ground.

Life and Death

Crows and ravens also serve as symbols of death, usually to mark the passing of an important hero. This is especially common in Celtic mythology with one prominent story being the death of the giant Bran the Blessed. Bran the Blessed, who’s name literally means Holy Crow the Blessed, was the God of Ravens and Prophecy. He would use his ravens as messengers between the mortal world and the spirit world. Bran the Blessed ruled over Wales and protected it from harm, until he fell in battle against invading Irish armies. His head was buried on the battlefield, so that his spirit would watch over his lands.

Later myths state that when King Arthur came to Wales, he dug up the head of Bran the Blessed to show that he could protect the land with his strength alone. Though his head was gone, Bran the Blessed’s ravens refused to leave the field, determined to watch over the land even with their master gone.

The association between corvids and death is clear; their status as scavengers made them a common sight on battlegrounds where they consumed the remains of corpses. Though the Celts took ravens to be a good sign, many other cultures viewed them as bad omens or warnings of a coming tragedy.

Today

In addition to the previous examples, corvids today are seen as symbols of magic, likely due to their association as messengers for gods or symbols of death. Bran Stark, a character from the hit book series A Song of Ice and Fire and the TV show Game of Thrones, is associated with crows and even becomes a magical figure known as the Three-Eyed Raven. He has the power to see into the past and future and uses crows as spies.

Even the legend of Bran the Blessed continues on to this day. The Tower of London is built where he supposedly is buried, and it is a popular roosting spot for ravens. One superstition suggests that if the ravens were to abandon the tower then Great Britain would be destroyed!

I hope you’ve enjoyed taking a closer look at corvid behavior in myth. What other examples across animalia can you think of?

I enjoyed this story very much. Thank you. Funny because I have a few crows here that spy on me. As I write this, one sits on a tree branch about twenty yards away looking into my window. He, at time, flys close to the window in a diving motion. I am assuming they have great eye sight. Again, thanks!