“Bird, above the snag, a glass up!”

Conversations halt as we all concentrate on locating a distant dot against the blue sky. Could it be a falcon? A Bald Eagle? Or perhaps the famed beauty of the Appalachian flyway, a Golden Eagle? The voice of raptor expert Nick Bolgiano punctuates the silence with confidence. “That’s a Golden Eagle.”

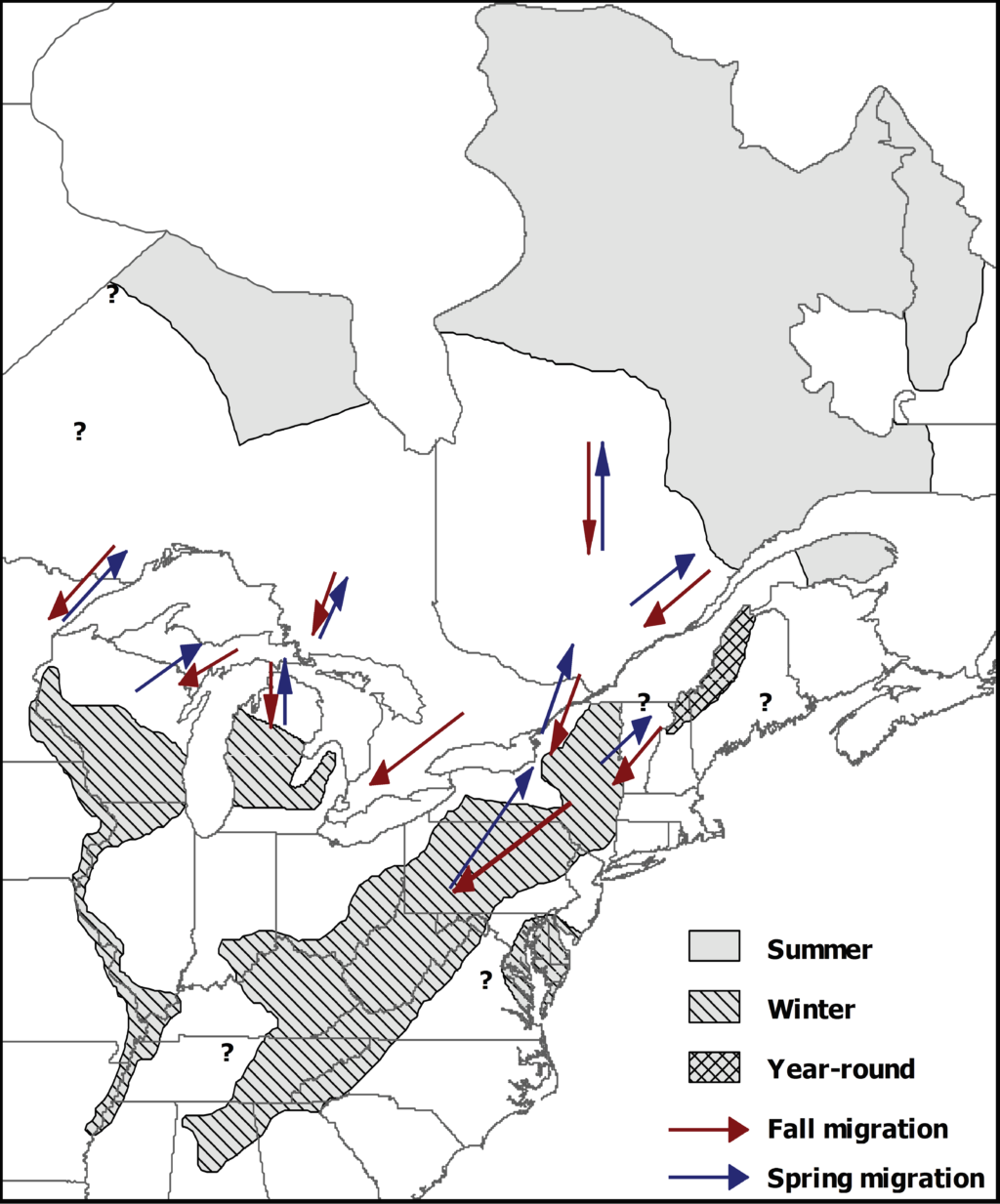

We are perched atop Tussey Mountain, the site of an avian mystery that is slowly but surely unveiling itself to a group of eager investigators. Every spring, Golden Eagles complete an arduous journey from the southern Appalachian Mountains to their breeding grounds in the Canadian Arctic. By watching the sky from March through April, Nick and his fellow raptor enthusiasts have verified that Tussey Mountain provides updrafts that are used by eagle migrants looking to save energy on their way north. Currently, Tussey Mountain Hawk Watch records the highest numbers of Golden Eagles east of Michigan, a fact that makes central Pennsylvania’s topography something to be grateful for.

This spring, I was the Tussey Mountain Hawk Watcher. In other words, I lived outside from 9–5 with the sun, wind, hail, snow, rain, thunder, and birds as my constant companions. Life was good. And, life was different.

Mornings began with a short hike, setting up “The Throne,” acclimating my Kestrel weather tool, and chugging some coffee to help my non-data brain transition into a data brain. Next, I would greet the regulars — chickadees, ravens, and vultures — and turn my eyes upward.

Being a Hawk Watcher is a unique experience, filled with opportunities to cultivate a sense of introspection that I believe to be otherwise unattainable. This new sense of self has been exemplified by the simple fact that I now have a relationship with the sky. The blankness above has become a canvas of possibility that holds undiscovered birds behind every cloud. This season, it was up to me to find them. It was up to me to name them. It was up to me to bid them farewell. Through the simple task of watching the sky, I was swallowed into it — wings, wind, and all.

I watched natural history unfurl as winter closed and spring began. The change was apparent in the mouth of a raven as it carried a chipmunk to its young, in a baby milk snake that wound itself through my fingers, in the Red Maples that now paint the valley, and in the warblers that appeared during my final week. Change was also apparent in my wardrobe.

The mountain even affected my personality. Friends would call me extroverted, yet I found myself basking in the solitude, sometimes staying an extra hour just to prolong the juicy quiet. Those same friends know me to erupt into nonsensical and colorful cursing over things like spilled coffee, broken pencils, and splinters. However, these events occur every day on the hawk watch. I smashed fingers beneath rocks and dropped valuables into no-man’s land. I had days where the wind knocked me sideways so many times, I had to sit down. These “mishaps,” became part of the mountain’s wild nature and they forced a tranquility of spirit that has oozed into the rest of my life. In other words, thanks to the hawks, I am now zen.

As a Hawk Watcher, I became reacquainted with raptors. I have been fond of predatory birds for a long time, with their slicing talons, keen eyesight, undeniable power, and smooth aesthetic. Yet to know a creature as only powerful, is to know it in only one dimension. Migration is perilous and risky — even for large raptors — and seeing these mighty birds during a moment as vulnerable as migration, was to know them more deeply. They became multi-dimensional beings with more than just meat on the mind. My image of raptors is now rounded out with a tinge of realism and the recognition that even the most ruthless of predators face moments of uncertainty.

One of the greatest joys of this job, however, was the social component. Given the current unrest in our world, I witnessed a stark increase in the perceived value of the outdoors during my time at Tussey. As the virus spread and lockdowns were initiated, people turned to the trails. Pent-up explorers would stumble upon the lookout, find me staring at the sky and follow my gaze. Next, they would become their most curious selves.

“Wait, birds migrate?”

“Wait wait, eagles migrate here?”

“Aren’t you freezing?”

“How long do you have to be out here?”

“How can you decide which birds to count?”

“Do you have enough to eat?”

And my personal favorite, spoken by some who discovered migration only moments before, “Thank you for doing this.”

I watched visitors develop confidence in identifying vultures after a mere 10 minutes, trotting away with their heads up and a smile on their face, proving what I have argued for years, that vultures can bring people joy.

I overheard kids saying the most profound things. “Mom, Dad, what are you most afraid of?” “How does our subconscious make us smarter?” “Mom, I think I’m ridiculous.”

I had the privilege of witnessing my boyfriend Jason successfully identify his first eagle. Now, he’ll have no choice but to love birds, which was my plan all along.

I met a hiker on his final mile of a long journey to raise money for COVID. I spoke with teachers seeking a momentary reprieve from the trials of online teaching. I gave impromptu ornithology lectures to eager pupils with the rocks for chairs and the sky for a classroom. In exchange, I received oranges.

I watched my mentor and friend, Jon Kauffman, become a father before my very eyes, sharing his love of nature with his nestling who will grow up with eagles next-door.

I spent impactful hours philosophizing about migration science with raptor-expert Nick, and now have a bank of “Nick Quotes,” ready for future use. “Being up here is just like yoga class.” “Can you believe we get to be here in the wind for free?” “It’s APPLE TIME!”

Through responses to my daily reports, I have read memorable stories, poems, and heartfelt expressions outlining exactly why readers have come to cherish birds.

In essence, through hawks, I’ve known people.

The Appalachian mountains and the forests that surround them will forever be folded into my core. My evolution as a naturalist began in these mountains, and here I am, continuing to weave my heart into white pine and grapevine. I am a born and raised westerner, yet my journey from sapling to tree occurred here in the east, and this spring I have been grateful to live where familiar faces of birds and friends waltzed in and out. I will remember this season as the first time I took Aldo Leopold’s advice and tried thinking like a mountain. It is difficult, rewarding, and necessary. Thank you, Tussey, for all you have revealed to me.

And now, as my final “Greeting from the Mountain,” I will leave you all with a quote from Scott Weidensaul’s book, Mountains of the Heart:

“…but for now there is only the mountain, the feel of the chilly quartz through my shirt, the soft wind and the sweet light of sunset polishing the day. Time enough later for journeys; for now, the ancient pace of the mountains is enough.”